SCA Combat Curriculum Development - Skill Focus - Conditioning

Therefore there is no doubt at all but that a man's strength may be increased by reasonable exercise, And so likewise by too much rest it may be diminished: the which if it were not manifest, yet it might be proved by infinite examples. You shall see Gentlemen, Knights and others, to be most strong and nimble in running or leaping, or in vaulting, or in turning on Horseback, and yet are not able by a great deal to bear so great a burden as a Country man or Porter: But in contrary in running and leaping, the Porter and Country man are most slow and heavy, neither know how to vault upon their horse without a ladder. And this proceeds of no other cause, than for that every man is not exercised in that which is most esteemed: So that if in the managing of these weapons, a man would get strength, it shall be convenient for him to exercise himself in such sort as shall be declared.

- Giacomo di Grassi

Conditioning is, in this context, the required cultivatable physical attributes to perform on the field. No one starts in peak performance condition, if only because none of us grow up used to holding a quarter-sheet of plywood on our arm for extended periods. No two people have the same conditioning needs, either. Thus, it is important to assess one's own expectations and needs before trying to develop any program. Ideally, you'd consult with a trainer, and everything I say should be viewed through the lens of "I am not a lawyer" (or in this case, personal trainer - and conditioning is an area where I have for years struggled to find a good balance).

Conditioning is not merely a matter of endurance, flexibility, and strength, though those are definite cultivatable physical attributes. It also includes such matters as training the body to hold the sword in guard, the cultivation of proper stance, and the repetitive practice of the physical skills associated with fighting, to the point that they become automatic. The earliest western source to address this directly, to my knowledge, is Flavius Vegetius, in De Re Militarii. Vegetius is an unreliable source, unfortunately - he was basically a mid-grade staff officer arguing for a reform program and hearkening back to an idealized time and system that never existed. Basing training off of Vegetius is like basing training off the hazy recollections of a retiree who swears that soldiers these days are soft and in his day they hauled fifty-pound packs of rocks everywhere for two weeks before a field exercise to train up. Well, they might have, but you might want to investigate that further.

Be that as it may, we have a medieval paraphrase of Vegetius in the form of the Pell Poem, based off of the common practices of the age. Rather than include its whole text, because of its length, I shall instead provide a Wiktenauer link, and provide excerpts below. It is remarkable in that it includes a holistic approach to conditioning - there are recognizable cardiorespiratory exercises, such as running, strength training, such as with overweight arms and armor, and the use of a pell to train. Let's look first at its cardio approach:

And wightly may thei go IIII Ml. moo,

But faster and they passe, it is to renne ;

In rennyng exercise is good also,

To smyte first in fight, and also whenne

To take a place our footmen wil, forrenne,

And take it erst ; also to serche or sture,

Lightly to come & go, rennynge is sure.Rennynge is also right good at the chace,

And forto lepe a dike, is also good,

To renne & lepe and ley vppon the face,

That it suppose a myghti man go wood

And lose his hert withoute sheding blood ;

For myghtily what man may renne & lepe,

May wel devicte and saf his party kepe.To swymme is eek to lerne in comer season ;

Men fynde not a brigge as ofte as flood,

Swymmyng to voide and chace an oste wil eson ;

Eeke aftir rayn the ryueres goth wood ;

That euery man in thoost can swymme, is good.

Knyght, squye, footman, cook & cosynere

And gnome & page in swymmyng is to lere.

First, yes, it's in medieval English. It's not actually that hard to read; just read it aloud phonetically. This was before standardized spelling, but the language is fairly straightforward. The first lines tie back to the previous stanzas, which deal with the fact that combat is a trained behavior, but quickly we get to the importance of being trained to move, move quickly, and still have enough gas in the tank after moving to fight. I personally find the stanza on swimming fascinating - the most dangerous situations in which I have ever found myself all involved flood waters, and to see swimming recommended not only for exercise but also as a practical matter is a pleasant surprise.

Strength training is given less time:

Of fight the disciplyne and exercise

Was this: To haue a pale or pile vpright

Of mannys hight, thus writeth olde and wyse ;

Therwith a bacheler, or a yong knyght

Shal first be taught to stonde & lerne fight ;

A fanne of doubil wight tak him his shelde,

Of doubil wight a mace of tre to weldeThis fanne & mace, which either doubil wight is

Of shelde & sword in [con]flicte or bataile,

Shal exercise as wel swordmen as knyghtys,

And noo man (as thei seyn) is seyn prevaile

In felde or in gravel thoughe he assaile

That with the pile nath first grete exercise ;

Thus writeth werreourys olde & wyse

There are serious disadvantages to this approach - approaching the pell with double-weighted arms and armor, before learning technique, is a certain way of damaging joints and imparting bad technique. However, it should be pointed out that this is the first time that the poem specifies who is to do the exercise - in this case, "a bachelor, or young knight."

The remainder of the poem describes how to address the pell, how to strike at it and what to practice, and a bit of mental preparation as well - the pell is not to be seen as an upright wooden post, but as an enemy combatant. Finding a visualization exercise described in a medieval text is rare, but it is a valuable point, from personal experience, that the closer you can get to actual fighting conditions in training to fight, the more useful the training is in an actual fight.

That's one source, and it has valuable information about what they thought mattered to a fighter. Contrary to our image of medieval knights conditioning by doing, it displays training as something that happens before the fight, both in and out of armor (note that swimming in armor is not recommended). Is this our only source regarding training and conditioning for fighters? Funny enough, no. Giacomo di Grassi has an entire section of his manual - and another Wiktenauer link, because of length! - on how to train the arms, the legs, and the feet. I find that di Grassi's arm exercises are potentially dangerous to the joints, but first, we know more about, and care more about, repetitive-motion injuries than period authors did (remember the double-weight sword?), and second, the point isn't that their programs were ideal, it is that they were thinking about the problem.

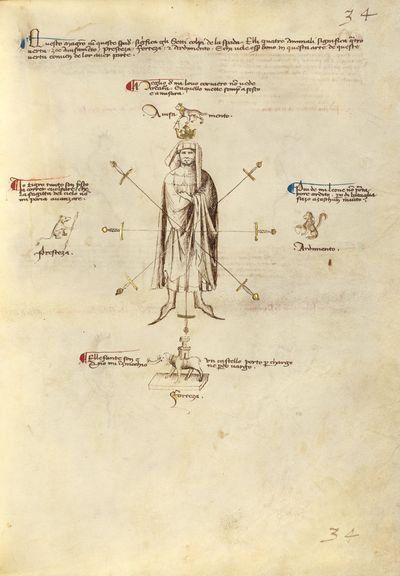

And, of course, there's This Guy.

What, you didn't expect to escape this post without a Fiore reference, did you? He makes pretty pictures. The four compass-point animals are descriptions of a swordsman's virtues, according to Fiore. Note that Fiore makes no moral judgments in his manual, so that these are not the Church's virtues; it would be hard to make moral judgments given that he was seeking the patronage of a proto-Renaissance Italian nobleman - Machiavelli would write The Prince only a hundred years later. No, these are the virtues of a swordsman, and are things that a swordsman should work towards, therefore they are trainable. The virtues are, from the top...

Prudence/Wisdom

No creature sees better than I the Lynx, and I proceed always with careful calculation.

Celerity/Speed

I am the Tiger, and I am so quick to run and turn, that even the thunderbolt from heaven cannot catch me.

Audacity/Daring

No one has a more courageous heart than I, the Lion, for I welcome all to meet me in battle.

Fortitude/Strength

I am the Elephant and I carry a castle in my care, and I neither fall to my knees nor lose my footing.

Of these, two are physical and two are mental. Strength is particularly interesting to me, based on Guy Windsor's comments in his excellent Fiore commentary, From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice. He pointed out that Fiore's definition of strength is particularly a definition of strength of stance and position, and that there's very little in there about being able to carry a literal house, and much more about being able to maintain whatever is carried with stability and poise.

So we have talked about the medieval and Renaissance fighter, and what they viewed as the attributes that could be conditioned and some of their views on how to train those. The other source we have commonly used in this discussion is Paul Porter's Bellatrix book. He has an entire chapter in there about training, and much of it overlaps with the above, but what Porter has to say that is radically different from period sources is that he focuses much more heavily on flexibility and agility training in his recommendations. If Fiore considered forty years of the study of arms to be sufficient qualification, Porter's judo career stretches back to before his SCA time and we're now 53 years into the SCA's history, so Porter's continuing ability to function as a judoka is an endorsement by itself.

Finally, there's this bit of advice from Dave Lowry (a forty-plus-year practitioner of Japanese sword work, so relevant here), in one of his Black Belt Magazine columns (courtesy of his book The Essence of Budo):

You do not have enough stamina.

Lowry is describing martial-arts matches where score is decided based on contact, and rarely extend past a couple of minutes. That sound familiar to SCA fighters? I know very few SCA fighters who train to have enough gas in the tank. That's not a call-out; I'm one of the ones who don't. I have yet to find an endurance exercise routine that I both don't hate, and can indulge (I love to swim, in all temperatures, but good luck fitting a side trip to the pool in a crowded schedule, or finding a year-round pool in Texas... so instead I hike).

So how does one train conditioning?

Some of it is so simple it probably doesn't need stating, but I've been That Guy (as opposed to This Guy) often enough that I'll state it anyway. First, you identify what you want to work on. Then, you either do that thing, or you develop an accurate simulator of that thing. To train stance, for instance, I use a standing desk at work and just stand there. I worked my shield arm by carrying groceries in position and opening doors with that hand while doing so. I've trained footwork between my desk and my bookshelves, or just moving around the kitchen. Dogs are great footwork trainers. I don't know a single SCA fighter who does not occasionally just sit there, often unconsciously, throwing shots, trying to smooth out the mechanics. The more accurate the simulator, the more effective it will be; for instance, my knight, who got his start on the rapier field (for context, his don was Iolo, and Iolo's don was Tivar, and if those don't mean anything, let's just say he started when I was three), swears by a wrist-strengthening routine involving a dowel roughly the size of his rapier grip, used to winch up a full gallon jug, because that's about twice the weight he'll ever use on the field, working the full range of rapier wrist movements.

Once you've done the thing, or the simulated thing, for a period, you see if you've gotten any better at it. If you haven't, you adjust what you're doing; if you have, you adjust the difficulty. Windsor describes this latter process pretty well in his Theory and Practice of Historical Martial Arts (not to be confused with his Fiore commentary), talking about how, if he's working with someone of lower skill, he may deliberately pushes himself into a position where he has to work to give them credible resistance, generally at the very edge of his balance.

Some of "the thing" is harder to train this way than others - cardio and endurance training, for instance, pretty much requires a dedicated cardio and endurance routine, even if that routine is something like Guy Windsor's breathing exercises. It is very difficult to push the limits of how much oxygen you can scrub out of a lungful of air just by carrying groceries; you really do have to train yourself to be vigorous and active under sustained load rather than just training to do a thousand push-ups once.

I would be remiss if I did not also add - do not do too much of the thing. Overdoing it is a great way to go beyond simply pain being weakness leaving the body, to coin an overused phrase, and into the realm of pain just being pain. My shoulder, for instance, frequently hurts for no reason from doing lots of bad pell work once upon a time. My knees were sacrificed to the Great Green Beast thanks to repetitive motion injuries years ago. Doing too much exercise, or doing an exercise wrong, will at best result in no progress, and at worst undo what progress you have made. Listen to your body (but don't give it the final vote - you can do a little more!).

Things that SCA fighters typically need to work on include how to stand in stance, how to hold a sword, how to move, how to throw a shot, and how to hold a shield for extended periods without losing control of the arm. Most of them will continue to be areas where conditioning is important even after the skill is mastered and ingrained, because there has never been a perfect swordsman. All of these can be illustrated at practice or in structured sessions, but they are also the kinds of things that really benefit from homework. Conditioning, more than any other skill including mental preparation, is an at-own-pace skill, because it is so heavily tied to individual needs. This is why Porter doesn't spend a lot of time on conditioning in his book or in his classes - it's up to him to teach, it's up to you to train.

This reminds me, it's time to set the standing desk up again...

In summary, conditioning is..

- The improvement of trainable physical attributes.

- Attested in manuals across the SCA period.

- Not simply endurance, flexibility, and strength, but also for technique.

- Better when it closely mimics the desired area of improvement.

- A repetitive process, not an overnight accomplishment.

On strength training, your knight also swears by the Big Three: sit-ups, push-ups and squats These are basics, not to be confused with sport-specific exercise.

ReplyDeleteOn aerobic training, my basic prescription is 30 minutes of motion at 80% VO2 max, 3 times a week. Swimming, running, stair climbing, biking, rowing, real or simulated on a machine are all good.The one you will actually do regularly is best. Advanced conditioning goes further, but this is a good start.

Very true. I deliberately didn't get into that, because, for instance, I have all the core strength I need but not enough leg or chest, and this was meant to be an overview and statement of intent, rather than specific. The milk-jug exercise was meant to give a sport-specific example.

Delete