A&S - On Female Japanese Names and the "Four-Kanji Problem" - Part II - Writing Systems, Speaking Systems, Female Names, and a Proposed Workaround

Last time, I discussed the four-kanji problem and the problem with medieval Japanese female names in the SCA - simply, they just don't get all the fun that men's names get in terms of wordplay and, in period, often look a bit like an afterthought in terms of naming. "My son's name is Noble Truth; my daughter's name is... uh... Pine Tree!"

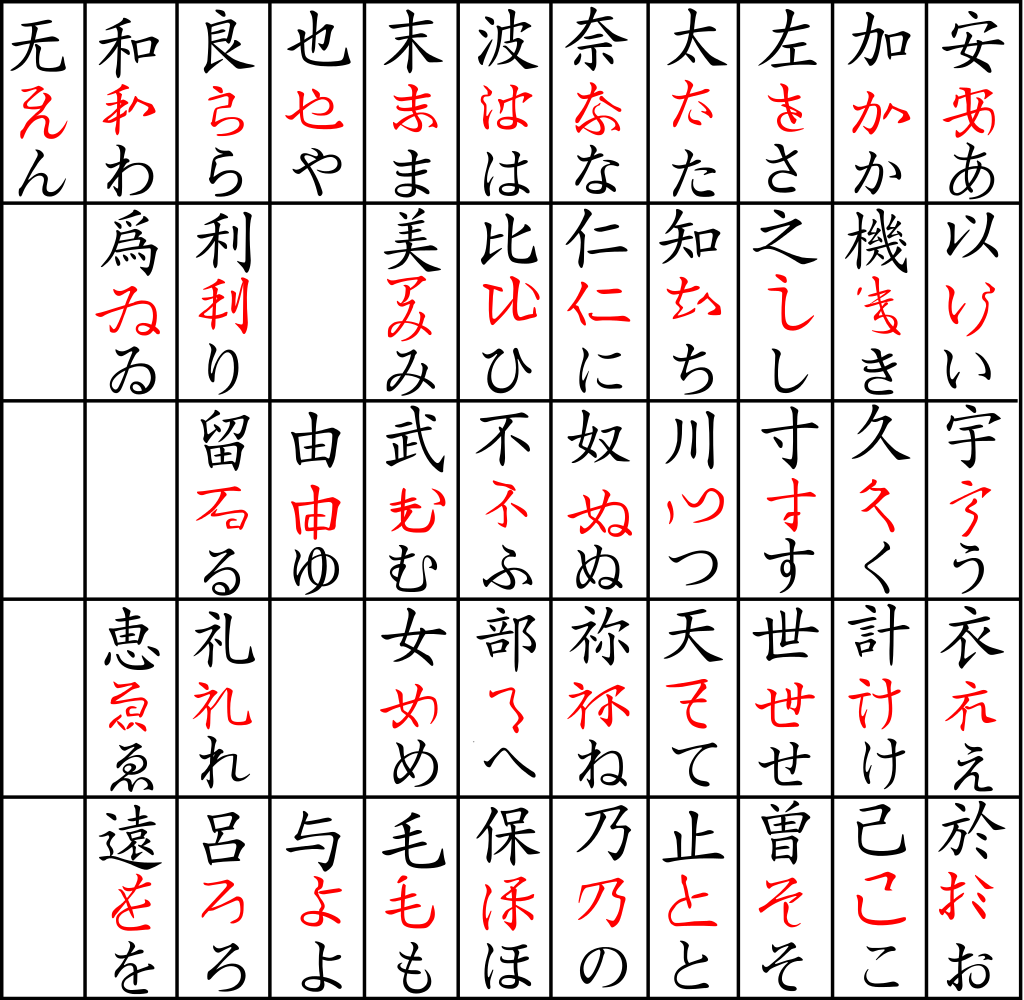

This time, I will discuss the four - yes, you read that right, four - writing systems found in medieval Japanese. First, and "best" in terms of prestige, is kanji, which is to say, Chinese characters imported during the earliest period of Japanese history and used based on their meaning. They may deviate from modern hanzi characters because hanzi have been simplified, and even here there are two forms, a "proper" form and a cursive form, which will be important in a moment. The second is manyougana - the use of kanji not for their meaning, but for their sound. Thus, the character 由 can be read as kanji, for "reason" (also for "yoshi") or it could be read in manyougana just for that leading "yu" sound. This was the first phonetic rendering of Japanese; the problem is that it is cumbersome and difficult to render at speed. Thus, two different systems of shorthand evolved. A monastic shorthand, katakana, or "cut-short characters," evolved for transcribing dictation. Widely considered a "masculine" writing system, it is noteworthy for sharp, angular characters and is today primarily used for foreign words and onomatopoeia. The

other, in this case more significant, is hiragana. Much of classical

Japanese literature was written in hiragana, mostly by women, which

allows us a guess as to how it was pronounced in the wild. Today, hiragana is, if not the primary way of writing Japanese, certainly the easiest to teach, because there is a not-quite-one-to-one correlation between hiragana and sounds, and the not-quite-one-to-one is mostly in foreign sounds and, for instance, kyu is "ki-shifting-into-yu." The modern hiragana writing of a word, and how to translate it back into manyougana, is a key point of the proposed solution below.

|

| Hiragana, with their manyougana origins |

Women's names are typically based off of virtues or natural phenomena; before, I gave "Matsu," or "pine tree," as an example. Non-aristocratic women typically led this with the polite "O-," so that "O-matsu" is a theoretically viable construction, but the "O" is not generally written. Noblewomen are where the more common modern "-ko" is usually found (Matsuko), with the most senior using "-hime," or princess, which is commonly found both as name and honorific; Takeda-san's name might be written as Takeda, but Matsuhime might very well be written as Matsuhime, even though the root name is still Matsu. The structure of Japanese words is such that they are in morae, typically in two or three morae with compounds stretching farther as needed, but the root words are generally two or three syllables. Coincidentally, men's names are typically two or three kanji.

My proposed solution to the "four-kanji" problem, therefore, is first to determine family names the old fashioned way, by identifying a nearby geographical feature, a city, or a town. Second, determine the root name you wish to use, such as Matsuko (or O-matsu or even Matsuhime). Third, take the hiragana construction of that name, convert it backwards into manyougana, and then assemble a name out of those. Consult Jisho or another character dictionary - Jisho is good because it gives name uses for kanji as well as simple meanings - and, if you want, make it either mean something or just sound good. For extra fun, flip the characters around or search for other characters that can also be pronounced as those syllables (there are nine single kanji uses of "yoshi" on the first page of Jisho results, for instance).

So let's look at poor Matsuko, who has decided to go become an itinerant ronin, because it's 1560 and it beats the hell out of warlords coming through every other month. Her root name is Matsu (まつ). The manyougana chart says that the source characters for those two characters are 末川 - which can then be copied individually into Jisho's search function to do a kanji search, and then look through names. Note that one of them for 末 is "Matsu," which should not be surprising given that manyougana originated in the phonetic sound of their lead syllable. Another, strictly arbitrarily chosen here, is Tome. The other one, 川, is almost universally used as a place-name as variants on "kawa." Unfortunately, Matsuko is likely at a dead end - but wait! "Kawa" can also be rendered as 革 - which is both a relatively common kanji and has a name component wherein it is pronounced "kaku." And away young Tomekaku goes! It's an ugly name, but it's also a passable warrior's nickname, since its components mean "stop" and "leather" or "rawhide." It isn't likely to hold up to close scrutiny, but this is an age when men with names like "Number 35" (Sanjuro) wander the land.

This is one of the workarounds; the other is to consult a broader table of manyougana characters, rather than the default one. From this, I learned that 都 is also used as tsu; it is also, through Jisho search, the name-component Kuni - Tomekuni is a slightly less ugly-to-the-ear Japanese name. This provides a way around the issue, but it is entirely possible that poor Matsuko is stuck with an ugly-sounding name. The point stands, though; there are a variety of manyougana characters that represent any sound, and a variety of kanji that can be used for most name fragments, and by twisting through combinations of these, one can arrive at any number of suitable puns, meaningful names, or other in-jokes.

Of course, there is nothing at all wrong with simply making one up out of whole cloth; this is merely an exercise in wordplay and to deal with the fact that women in medieval Japan are, if not precisely second-class citizens, still under-represented and there is at least one case - Ii Naotora, that straightforward tiger - where women did take male names. It is worth mentioning, because of the risk of erasure associated with this, that there are many more named cases of women in literally all periods of Japanese society; while we do not know Murasaki Shikibu's actual name for certain, we do know of Lady Okaji, who was said to have fought dressed as a man during the Sekigahara and Osaka campaigns.

The purpose of this entire exercise is more creative anachronism than anything else - Japanese women's names weren't constructed this way, and many of the names you will generate using this method, like "Tomekaku," are hideously ugly to the ear, but it also goes to show the flexibility of Japanese naming and re-naming, which could be quite useful for, say, establishing a new identity if one is sent to spy for one's lord. It is therefore not completely frivolous, despite its origins in my desire to find my daughter a way not to be called "colloquialism for lesbian" if she didn't want to be. Thus, Retsumura (either "Crazy Town" or "Gathering of Rage," depending on the day) no Yoshitoshi (I think) was born from the manyougana for "Yu-Ri."

Comments

Post a Comment