SCA Combat Curriculum Development - Skill Focus - Attack

Attack is the ability to hit a designated target with sufficient force to cause an impact. In SCA fighting, that impact is literal, as without sufficient impact, a combatant will not acknowledge the blow. In historical fighting, the impact varies between a touch - "a hit, a most palpable hit," according to Hamlet - and a severing of body parts, depending on circumstance and weapon type. In all cases, though, the fundamental mechanics remain the same, and we shall mostly confine ourselves to SCA combat in this blog, supported wherever possible by historical sources but acknowledging that there are certain game-isms associated with this.

The first of those game-isms is what counts as a hit. First, armor in the SCA serves its historical purpose of injury prevention, not its historical purpose of "there's no point in hitting me there;" contact to any legal target area has the potential to count. This is why both mail, which does little to prevent blunt force trauma, and plate, which is proof against the blow but not against being hit, are rare on the SCA list field; they are aesthetic choices rather than combat efficiency or safety choices. Compare this to Fiore's thoughts on armor (using Colin Hatcher's translation, from the preface to the Getty manuscript):

More than anyone else I was careful around other Masters of Arms and their students. And some of these Masters who were envious of me challenged me to fight with sharp edged and pointed swords wearing only a padded jacket, and without any other armor except for a pair of leather gloves; and this happened because I refused to practice with them or teach them anything of my art.

And I was obliged to fight five times in this way. And five times, for my honor, I had to fight in unfamiliar places without relatives and without friends to support me, not trusting anyone but God, my art, myself, and my sword. And by the grace of God, I acquitted myself honorably and without injury to myself.

I tell my students who have to fight at the barrier that fighting at the barrier is significantly less dangerous than fighting with live swords wearing only padded jackets, because when you fight with sharp swords, if you fail to cover one single strike you will likely die.

On the other hand, if you fight at the barrier and are well armored, you can take a lot of hits, but you can still win the fight. And here is another fact: at the barrier it is rare that anyone dies from being hit. So as far as I am concerned, and as I explained above, I would rather fight three times at the barrier than one time in a duel with sharp swords.

The difference is, of course, rattan isn't sharp, but the result is that, especially in hotter climates, fighters wear unrealistically little armor (they're not murmillones, after all, with a just manica and a helm!).

Thus, what counts as a hit can sometimes be an exercise in frustration and an exercise in interpretation. The assumed standard is more or less where I fight - mail shirt and a helm, everything else unarmored, and the idea is that people will have an idea what counts as a good blow. What, then, is "good" supposed to simulate? Is it the full-force blow of Sigurd Fafnirsbane who supposedly cleft an anvil in twain? Is it enough to disorient and allow capture, for ransom? Is it any contact at all, so long as the technique was properly executed and the targeting was good? The answer varies from person to person and fight to fight, and sometimes even from shot to shot within a given fight; one of my clearest fighting memories is of a knight I know landing what felt like a very light shot on me given what I knew he could throw, and I stopped and asked him what had happened, and he said the opening was there but he wasn't going to be an asshole. I happily yielded the point, because he had thrown a courtesy shot, and ignoring courtesy is a great way to collect bruises.

Because of these calibration issues, there is a certain minimum amount of power that is required to be taken seriously as a fighter, and though this doesn't reach the level of Sigurd and his anvil, every other example I have found indicates that the mechanics are enough to seriously injure a human being with a moderately sharp sword against an unarmored bit, and to cause serious concussive injury through a helm without proper padding - in other words, enough to satisfy Signor Fiore that we are out of our minds.

There are four fundamental types of attacks in the SCA; these are distinguished not by their targeting, because a forehand blow, or snap, can be delivered to any target on the body, but by their mechanics. These attacks are the knuckle-lead (snap), the thumb-lead (wrap), the thrust, and the hammer. Of these, the forehand or snap is by far the most common and most versatile, while the hammer is the least common and least versatile, being in essence a massively foreshortened forehand. Backhand techniques in SCA fighting are generally only executed to the opponent's back, thus the "wrap" monicker, but there are illustrations in Fiore that indicate backhand or false-edge techniques, mostly in the section on sword in two hands. Thrusts are a useful but deceptive tool, easy to get used to using in place of learning how to apply other techniques.

Strictly for the purposes of a new fighter, a knuckle-lead blow is the most common thrown, so it will be the focus of curriculum development; a fighter who has mastered the knuckle-lead can figure out the hammer pretty quickly, the thrust with a little more time, and the thumb-lead, because it involves the most spatial awareness and most reliance on proper technique to execute well, generally will be the last to fall into place.

As with steps, the mechanics of a knuckle-lead attack are deceptively simple in description, and painfully prone to mistake in execution. One of the most common mistakes is how to hold a sword. The beginner is tempted to death-grip it, like they are swinging a hammer or choking up on a baseball bat. This is improper; the sword should be "alive" in the hand, and choking it is not how you maintain that. Instead, the hand rests in a "handshake" grip around the hilt. Some fighters prefer to demonstrate this by holding the sword between thumb and forefinger, and letting it show its range of motion and grip this way. I have never found this controllable, and instead prefer thumb and ring or pinky finger if I am going to demonstrate how little hand is needed to control the sword. In either case, it is a matter of taste and personal preference, and it is entirely possible to guide a sword with a minimum of hand on the hilt.

I say guide rather than control, incidentally, for basic safety reasons - the sword, even a notional rattan sword, is a weapon, and deserves to be treated like it could kill, because even a rattan sword is a perfectly good club. Thinking that you know better than the sword is an excellent way of failing in its use, same as thinking you know the gun is unloaded is an excellent way of getting shot. You are there to guide the sword, not to force it, and forcing it is generally a path to joint damage, head trauma, or other undesirable outcomes.

In general, this is the sequence of events for such a shot. When training, I highly recommend identifying each of these steps in slow work until they are moving smoothly enough that they can become shorthand.

- Fighter is in stance and in range or moving into range. In training, I recommend a static start to focus on the following steps, then advancing to movement.

- Eye identifies target. In slow work or training, the brain or mouth can be engaged, but at full speed, the goal is to bypass these.

- The sword-side calf, thigh, and hip tense up, beginning the muscle chain. At this point, the sword-side hip is moving forward.

- The shield-side thigh tenses up, pulling body weight to the shield side and increasing the speed at which the sword-side hip rotates.

- The abdomen tenses up, linking the lower body and the shoulders into a rigid mass.

- The sword-side shoulder, which, as a reminder, is far back in a good stance, begins to rotate forward.

- At the same time that the sword-side shoulder begins to rotate forward, the sword hand comes forward, with the hilt and the knuckles pointing toward the desired target. The tip should be pointed away, either sideways or back; the sword needs to be able to rotate some around the wrist when the time comes.

- At the desired extension but never at full extension (great way to destroy joints), and almost but not quite in line with the target, the hand stops and the sword continues forward, so that the thumb points through the target. The wrist flexes and rotates at this point, letting the sword do all the work. At this point physics takes over, for reasons I will describe after the list.

- The sword makes contact somewhere in the last handspan or so from the tip, or the first handspan or so from the hilt in the case of a hammer. We call this the "sweet spot," and it is the point at which the greatest kinetic energy transfer without waste happens. In a hammer, much more shoulder and upper-body are engaged, just because of the short development lengths (try driving a nail with your hips, versus splitting wood with just your shoulder!), but the fundamental mechanics remain the same.

Why does physics take over? Because momentum is conservative - it can't be created or destroyed, only transferred. If, at point eight, the entire momentum of a human body most efficiently using the muscle chain through legs, hips, core, and shoulder, and using the rotation of the torso, is suddenly transferred to the much, much smaller sword, the sword accelerates through its last arc and into the target.

It is very tempting to swing through a target as you would with sharps, and to a very small extent this is desirable, but keep in mind that SCA heavy combat is basically a game of tag, played very hard. The focal point of the impact shouldn't be the other side of their head, it shouldn't be the Earth itself in a falling strike, it should be just inside the impact surface. You're cracking a whip, not swinging a mallet.

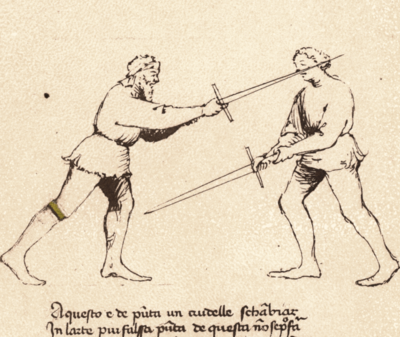

What does this look like in a period manual? Well, as it happens, Fiore once again has a perfectly good illustration!

Colin Hatcher's translation of the Getty manuscript:

When a sword flies for your leg

Make a downward blow to his face or around to his throat:

His arms will be wasted more quickly than his head,

Because the distance is manifest for a shorter time.If your opponent strikes to your leg, withdraw your front foot, or pass backwards and strike downwards to his head, as shown in the drawing. With a two handed sword it is unwise to strike to the knee or below, because it is too dangerous for the one striking. If you attack your opponent’s leg, you leave yourself completely uncovered. Now, if you have fallen to the ground, then it is all right to strike at your opponent’s legs, but otherwise it is not a good idea, as you should generally oppose his sword with your sword.

There is obviously not a shield here and the sword is two-handed, but the mechanics of a snap are on full display. Points to note in this picture...

- Scholar (on the right)'s grip is clearly precision or "handshake" grip, not hammer grip. Note how the thumb lies parallel to the fingers, not over the fingers.

- Master (on the left)'s weight is intentionally committed.

- Master's back leg is tensed from foot to hip and on the ball of the foot.

- Master's front leg is tense in the thigh but not completely straight.

- Contact is with the knuckles leading for both players.

- Master's sword arm is not fully extended; there is bunching in the fabric at the elbow.

- In the text, there's a clear correlation between target identification and response.

- In the text, there's also a clear awareness of measure - the effective attack range.

Now, note that in all of this, I have assumed that the sword stops moving at point #9. That's intentional; it's also false. All that the above list is meant to do is walk through which muscles mobilize, and in what order, and to get the shot launched downrange. The sword needs to come back to the body; it can either return to guard, or it can be pulled back using a twitch of the hips - hips are critically important in this kind of fighting - to apply the torso and upper body's momentum to the blade to bring it back.

And since twitching the hips to pull the sword back chambers another shot - why not throw another shot? For that matter, why not simply change which hip is being used to drive the shot, and throw a shot from the other hip? Why not throw a shot using a step to generate that momentum? These are all perfectly valid ways of firing the next shot, and should be explored in great depth, but one of the criticisms I've made of the Bellatrix book is that he spends a lot of time on variations, so I will leave those as an exercise.

Instead, I will discuss the other shots - the wrap and the thrust. The wrap is easily the most painful shot to train, at least for me, because my arm simply did not want to move the way my knight described. It liked to follow the sword. I'm still not certain my way is right, but it functions.

The difference between a snap and a wrap, as I've described, is where the hand is and how the wrist "breaks." For either snap or wrap the hand needs to be about a sword-length away from the target, but unlike the snap, where that sword-length is between you and the target, for the most part in a wrap the hand has to be located away from the body, and the wrist has to go through a much more violent rotation. The sword still starts pointing away from the target, but when the wrist "breaks," instead of the knuckles leading in toward the target, which leaves the fingers more or less in line with the long bones of the forearm, the thumb leads, which means that the wrist goes through about 3/4 of its range of motion instead of 1/4 for the knuckle-lead, and the fingers often rotate past alignment with the long bones (practice this without a sword in your hand, just moving the wrist, and you'll see what I meant). Stretching way back to my martial arts days, it is the ridge hand to the knuckle-lead's chop, and in both cases, the most useful thing I've found is to remind myself "noodle arm," rather than trying to fight it into the target - remember, you guide the sword, not control the sword.

The thrust is exactly what it says on the tin - an attack with the tip of the sword. The danger with thrusts is that unless they are delivered hard, with vigor, they are often unnoticeable. Thus, even with the thrust, a drive from the ground, through the hip, is necessary, and often fighters will not call any thrust but those to the face - although I've found a cup thrust is also hard to ignore, it's not an attack I generally deliver deliberately. Courtesy, after all, goes a long way.

I hate to do this, because it drives me nuts when, say, Musashi does it, but at this point, everything that can be described is described, and you have to go out and actually do it for it to make any sense. Even watching it in video - and Paul of Bellatrix has some excellent videos for this purpose - isn't the same as feeling how your body moves through it.

How do you train technique?

Well, start off with a partner. Practice the basic movements on a pell or a stick held by the partner, and start off slowly. If you're not bored in training, you're not training enough, and if you are bored in training, you're not pushing your training hard enough. As the movements get smoother and more ingrained, do them faster or introduce variations - "good, now leg" or "offside ribs now" for instance. When the technique is firmly enough established that it can be moved to drill work, do partner drills, again slowly, and build up from there. I recommend, if possible, taking a video every month or so, so that you can see your progress, otherwise you get stuck in a rut where you think you're incompetent after three or four years of slow but steady improvement... not that I'd know anything about that.

So, to summarize, an attack:

- Can be delivered in multiple ways, and should look for the most efficient path to the target.

- Should be delivered with sufficient power for an opponent to feel the attack regardless of armor worn.

- Uses the maximum number of muscles allowed by the chosen movement to involve the maximum percentage of body mass to hit the opponent.

- Depends heavily on proper body mechanics, starting from the grip and moving through the muscle chains, to mobilize power for points 2 and 3.

- Needs practice and repetition to learn, and a suite of variations to master.

Comments

Post a Comment