SCA Combat Curriculum Development - Skill Focus - Stance

Stance is the foundation from which all movement, attack, and defense must proceed. Therefore, while it is easy to overlook specific training in it, stance and body position should be built into every lesson.

What points do we have available for stance from period sources? First, we need to recognize that most illustrated historical texts do not have dedicated "stances" in the sense of which foot goes forward as a matter of principle, they tend to illustrate what is best in that moment of the fight. For instance, in the figure below from MS I.33, the priest (tonsured) is fighting shield foot forward, while the scholar (hooded) is fighting sword foot forward. Elsewhere in I.33, the priest commonly fights sword foot forward.

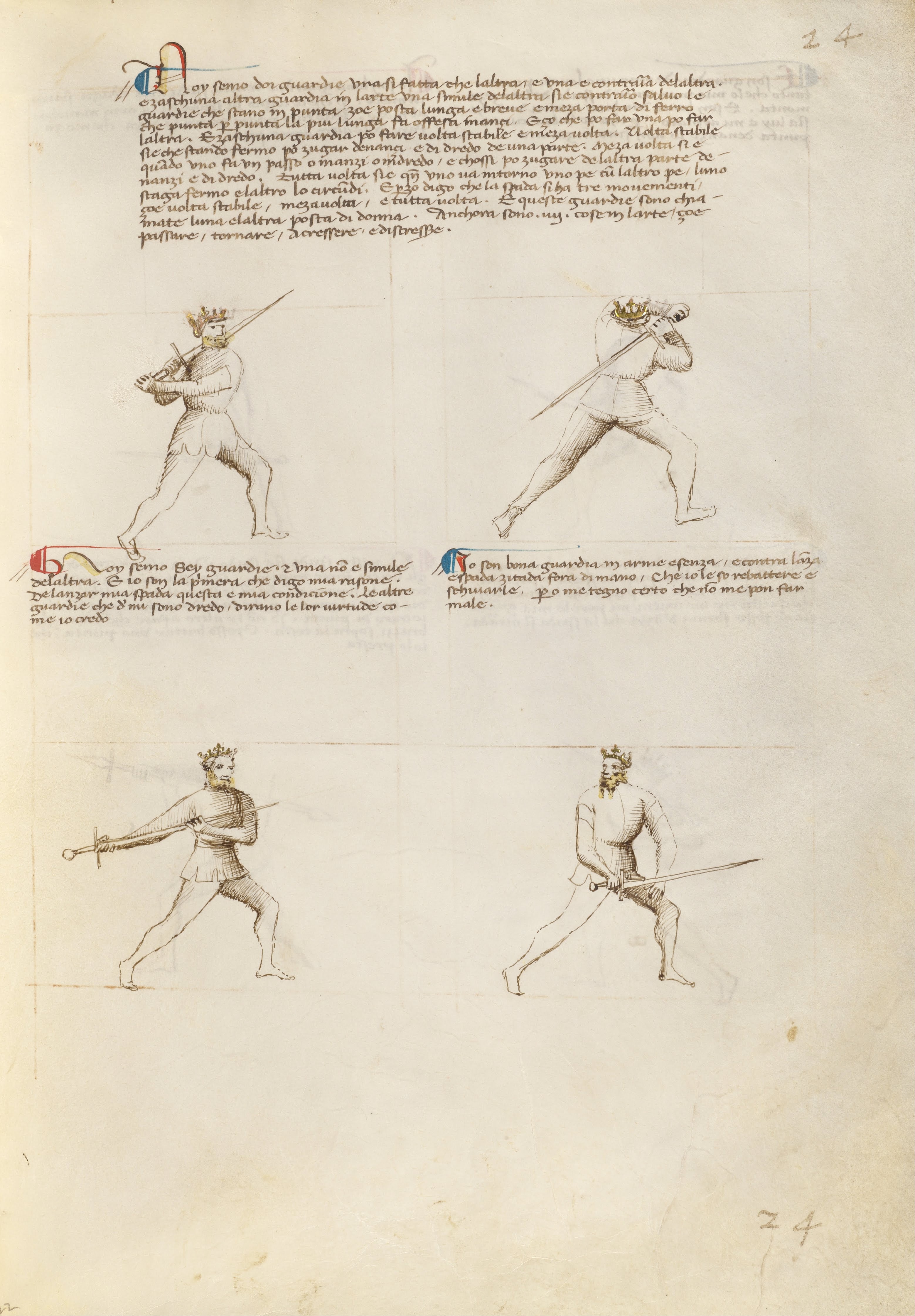

Similarly, foot position changes regularly throughout Fiore and Talhoffer; Fiore is especially significant because he demonstrates that foot position is secondary to him to weight distribution in the first two panels of 22r - note that the master in the top-left is "shield" foot forward and his weight is distributed more or less evenly between the balls of his feet, and the master in top-right is sword-foot forward and leaning heavily into his lead foot. The accompanying text in the upper block, according to Michael Chidester and Colin Hatcher, follows the image.

We are two guards that are similar to each other, and yet each one is a counter to the other. And for all other guards in this art, guards that are similar are counters to each other, with the exception of the guards that stand ready to thrust—the Long Guard, the Short Guard and the Middle Iron Gate. For when it is thrust against thrust the weapon with the longer reach will strike first. And whatever one of these guards can do so can the other.

And from each guard you can make a “turn in place” or a half turn. A turn in place is when without actually stepping you can play to the front and then to the rear on the same side. A half turn is when you make a step forwards or backwards and can switch sides to play on the other side from a forwards or backwards position. A full turn is when you circle one foot around the other, one remaining where it is while the other rotates around it.

Furthermore you should know that the sword can make the same three movements, namely stable turn, half turn and full turn.

Both of these guards drawn below are named the Guard of the Lady.

Also, there are four types of movement in this art, namely passing forwards, returning, advancing, and withdrawing.

That panel is also most of what Fiore has to say about footwork in general. It should be sufficient, from these two examples, to demonstrate that period manuals' approach to foot position is fairly casual. This is, again, not because it was trivial to them, otherwise Fiore wouldn't have said anything at all, but because it was likely assumed that, with arms being a skill that most gentry picked up from a fairly early age, foot position and footwork was drilled into them. After all, look at the very open stances taken in both I.33 and Fiore, especially that Fiore gives those positions as where he would start a play - that speaks to a tremendous control of the leg muscles, and that does not develop in a vacuum.

However, modern legs don't work that way, through a combination of factors possibly including artistic exaggeration to emphasize a point. These factors include different muscle groups emphasized by our lifestyles (we squat less and sit more), different training conditions (most modern martial artists don't start from near birth), and different training emphases, especially among westerners, where the upper body tends to get prioritized (not that Fiore didn't prize upper body strength - look at the thickness of the upper arm in the top-right panel, and the broad shoulders of all four fighters).

Instead, most modern fighters prefer a more upright carriage; there is nothing at all wrong with that, so long as it is trained consistently and well, and the stance encourages the most efficient possible use of resources. These resources include:

- The ability to shift weight in any direction at any time.

- The ability to conceal as much meat behind defense as possible.

- The ability to generate the longest possible chain of engaged large muscles for power.

- The ability to breathe freely.

Of these, at least the first three start at ground level. It is worth looking at the foot stance of most boxers. Let's look at Muhammad Ali as our example - hard to go wrong with the Greatest of All Time, after all.

This is the "orthodox" stance in boxing, as opposed to southpaw. The orthodox stance keeps the dominant hand, in this case Ali's right, back. Most right-handed fighters prefer orthodox because more of the body's long muscle chains can be mobilized when that right arm fires. Note that Ali's body is mostly concealed behind his hands, and that the hands are not fixed. His legs are open, and not in line, allowing his hips to mobilize fully, and his feet are shoulder-width apart. The lead knee is slightly bent; I would expect more bend in the back knee, but on activation, the back calf, thigh, and hip will tighten, the core will tighten, and the right hand will fly forward basically on its own. With the exception that we have a stick in that hand, and a shield on the left arm, that's pretty much how a snap works.

There are two other very noteworthy points in that photo of Ali - the shoulder and the spine. His right shoulder is deeply refused; that is, it is far back, and his shoulders are relaxed without being slack. This relaxing of tension in the shoulders helps to keep air flowing into the lungs, helps maintain spinal alignment, and helps not rob power from the arms when they go forward. In other words, it helps him spend less energy to fight the same length of time, meaning his reserves burn at a lower rate per minute and his fight lasts longer (Ali and Fraser famously went all fifteen rounds - a full hour of active combat - in Ali-Fraser I, and they both looked like death after). The other noteworthy factor is the spine. An erect spine, from the base of the skull to the tailbone, is another key to mobilizing the entire chain of large muscles from calf to shoulder; hunching the spine or crouching in short-circuits that chain and even if all the other mechanics are correct, only the muscles from the point the spine is bent upwards get in the game when the shot starts moving.

Compare those shoulders, and that spine, to the I.33 priest, and Fiore's masters. Especially in posta di donna, the guard the first two masters take, the shoulder is deeply refused, but all of Fiore's masters are erect and upright (note the back seam on the top-right master's pourpoint!), and the priest in I.33 has a straight line from the back of his head all the way to his heel. Even where it's not being directly referenced, these principles are still visible in their work. The only difference is that they need to be laid out for the modern student.

The last piece of stance is the hands. This, I fear, is where that photo of Ali, and the period masters, fall apart in our game - not that Fiore's arms and hands are bad, but if you're fighting sword and shield, posta di donna doesn't tell you what to do with your left hand. It's a perfectly valid, even excellent, way to generate power because it forces deep shoulder refusal (matter of fact, we call one-handed posta di donna the Bellatrix stance), but what's the free hand do?

Well, it keeps you from getting hit fatally, that's what. First off, it's easier to live without an arm than without a head, so the "off" arm is, by nature, a sacrificial lamb. Second, that's the arm you have a shield on. It therefore is forward of the body, but not too far forward, because despite what I.33 might indicate, shields get heavy fast, especially if you're not used to holding them. There is no one right answer to how to hold your shield, and much of it is dependent on shield shape, size, and strapping - for instance, my stance has unwittingly evolved to look a lot like Ali's, except that my sword hand is in front of my left eye, with my shield angled slightly, but my knight fights with his shield and sword hands basically centered in front of him, and his shield flat facing me, and my son fights with his sword level left-right a hair above his eye line and his shield centered in front of him. What matters most is that you do it consistently, worrying less about shield position and more about body position behind it, and foot position beneath the body, because until you have those mastered, fighters will find openings in your defense, but once you have those mastered, tightening the defense up is fairly trivial.

So that's one hand; hopefully if you read where our hands were in the immediately preceding paragraph, you picked up that our sword hands are also not in the classic Bellatrix/posta di donna position. This is partly because the state of practice has changed since the Bellatrix system was invented, and partly because if I try to fight in that stance I get clubbed in the head a lot more than if I fight the way I do. I evolved mine out of earlier tae kwon do experience, and my knight basically evolved his on his own because no one fought center-grip when he was learning it. All three of the positions I described above can be used for generating power, but the commonality between them, and the most efficient position for generating power, is that the sword shoulder is refused, and the spine in alignment. Everything after those two factors is personal preference. I've seen a successful fighter whose guard involved his sword arm basically giving a thumbs-down from directly above his head to a point directly in front of his face; it seems unnatural to me but I see how the mechanics of it would work.

To summarize - points to emphasize in a conventional shield-forward stance, as a default:

- Feet about a step, maybe a little more (or as far as you can manage while able to shift weight!) apart front-back.

- Feet about shoulder-width apart left-right.

- Front foot angle between straight forward and slightly toward sword-side.

- Back foot about 45 degrees off straight forward.

- Knees bent, but not to a point where the stance is impossible to hold for long periods.

- Weight centered between the two feet.

- Spine straight - if knees are bent to where it matters, angle the buttocks and tailbone to maintain this!

- Sword shoulder deeply refused.

- Shield hand positioned comfortably in front of the body where the shield's weight is not constantly being carried by the arm.

- Sword

hand positioned where it will not negatively impact that shoulder

refusal or spine alignment - otherwise, wide range of valid positions.

Comments

Post a Comment