SCA Combat Curriculum Development - Skill Focus - Defense

Defense is simply that which prevents one from being harmed. In the context of SCA combat, it can be divided into three sub-categories: armor, deflection, and mobility. As mentioned in my discussion of attack, armor plays very little role in protecting the SCA fighter or a HEMA tournament fighter - the assumption is that a blow is good when it hits the body. There is a great debate that could be had about the correctness of this interpretation, but that is the game we play. Deflection, meanwhile, is most of what shields do - blocking attacks from reaching the body in the first place. Finally, mobility is the art of not being where the blow lands. Because great weapons, two-handed weapons, and two-weapon fighters have much less to work with on defense, this is where their defenses tend to focus.

Our period sources for defense tend to focus on two kinds - deflection, in the form of parry, and mobility, in the form of steps off the line. Part of this is because by the time we see fechtbucher being written, the state of the battlefield had evolved away from the use of the single-handed arming sword as anything but a mark of social standing. Thus, we see only a couple of manuals that feature shielded fighting - notably Talhoffer and I.33. Even so, the shields used are bucklers or, in Talhoffer's case, dueling shields that don't correspond to anything used in SCA combat. Where we do see armored fighters using shields, such as in Adam van Breen's 1617 drill manual for armored soldiers, we do not see behavior that would work in an SCA context. An example:

The 1625 English translation of the above posture:

Gard yor. self.

How to gard himselfe well, he must hold his Target before him against his left knee and shoulder firme to beare of the shocke or downe right blow and on the right hippe susteine himselfe with the hilt of the sword, till he may use it.

Having fought in a shieldwall, that's actually pretty good advice for how to use a shield in a wall - position yourself as a human shock absorber. I'd reposition the right foot to avoid blowing the knee out, but this is a reasonable starting point. However, the position of the sword is terrible for SCA combat. The left side of the head is completely exposed and repositioning the hand or sword in order to cover that gap is going to eat up precious fragments of a second. He can get away with that - he has a closed full-face helm that will likely stop anything that a sword would deflect anyway. In SCA fighting, the helm's purpose is to prevent injury, a good blow to a helm is still a good blow.

So - that's a period-adjacent illustration showing their thoughts on how to hold a shield in combat. The shield shape is basically a long strapped heater, with no Polish wing or any other strange features, and covers slightly more ground than is covered by a standard SCA shield. It will provide plenty of what we refer to as "static" defense, meaning that so long as the arm holds it, that part of the body is basically closed. It is, in other words, a passable start point for what period sources say about defending yourself with a shield, and where it would not work in the SCA because of SCA rules versus battlefield rules.

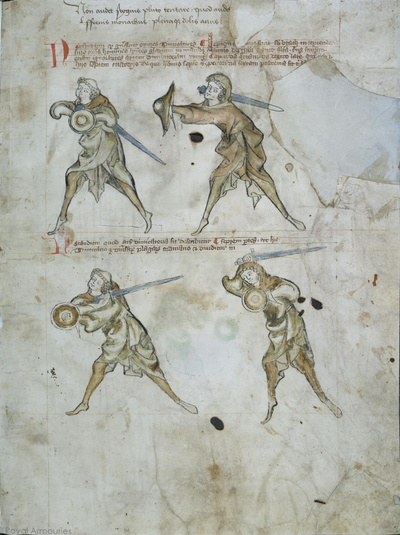

I've repeatedly mentioned I.33, so let's look at it as well, because the combat conditions depicted by I.33 - where the "strike zone" is, so to speak - are about the same as the SCA's conventions. If either priest or pupil gets struck between head and knee, they are going to call the blow, because those are sharps. I.33 is a sword and buckler manual, and most of what it has to say about bucklers holds much later, as far at least as Capoferro in the late 1500s. Because the swords of I.33 are arming swords, it also shows the kinds of strikes that we are likely to use, rather than rapier.

|

| MS I.33, Folio 1r - "Fencing is the ordering of various strikes." |

Translation, per Dieter Bachmann:

Note how in general all fencers, or all men who hold a sword in hand, even when ignorant in the art of fencing, make use of these seven guards, on which we have seven verses:

Seven guards there are, under the arm the first

On the right shoulder the second, the third on the left

To the head give the fourth, to the right side the fifth

To the breast give the sixth, and as the final one have langort.Note that the art of fencing is described as follows: Fencing is the ordering of various strikes, and it is divided into seven parts as here.

The first four are what are depicted here; the following page has the next three, but one is enough to get the point here. The position of the sword is in a series of practical positions for SCA fighting - the two right-side figures are viable versions of Paul Porter's Bellatrix stance, with the sword deeply refused for power generation. If the sword hand is forward, the buckler is protecting the sword hand - without the sword hand, after all, you're much more vulnerable - and if the sword hand is back, the buckler is as far forward as is practical. The bottom-right figure is interesting to me, because it looks like the buckler is chambered for a punch-block, which I will get to later.

These two examples are sufficient to illustrate, as Fiore's comments about armor that I've quoted elsewhere say, that there's a difference between fighting in armor and fighting where everything is a target. SCA rules basically dictate that everything is a target, and this is important in developing a defense - what do you have to protect? Everything, in short.

So much for period sources on deflection with a shield, and the mindset associated with it. Let's talk about their views on deflection with a sword, better known as a parry. Fiore discusses this in detail, dividing the sword into thirds and saying that the third closest to the hand can deflect a little, the next third less, and the last third, none; thus Fiore prefers what I think of as a "shedding" parry, versus a hard parry. Worth note - Fiore's sword division is roughly the same as the fencer's division into forte and foible. Despite what is widely believed, Japanese sources also recommend parrying where the sword is structurally strongest, though they use the guard less than the more-developed western quillions; Yagyuu Munenori's preferred parry for the textbook downward-strike killing blow was to parry and, if the opponent was likely to blow through the parry, to half-sword and brace the blade. Essentially all of German longsword revolves around an aggressive parry and using it to establish the initiative - vor and nach are flexible in their system, and rely on who can seize the initiative, usually by driving the opponent's sword into a disadvantageous place.

I want to spend a moment longer on Fiore, because he's the first theorist who talks about the "line." The line is the simplest path to land a successful attack. All of Fiore's guards - indeed, all sword guards - are designed either to close lines outright, or to make it easy to close those lines. Fiore calls this a "cover." To show how this works, I'm going to commit a minor sin and mix two different Fiore manuscripts. The first, with the Master in crown, is from MS Ludwig XV, the "Getty" manuscript; the second, from the Pisani Dossi manuscript. I mix them because I don't have access to a complete Getty here, and the illustrations are sequential. As always, text blocks will follow the illustrations and, as always with Fiore, are from the Hatcher translation. The situation is that the Master, shown first, is in the Lower Iron Gate, with the point almost on the ground. Note that the sword is in one hand, and the sword shoulder is deeply refused despite the fact that the attackers are coming at his back.

Whether throwing the sword or striking cuts and thrusts,

Nothing will trouble me because of the guard that I hold.

Come one by one whoever wants to go against me

Because I want to contend with them all.

And whoever wants to see covers and strikes,

Taking the sword and binding without fail,

Watch what my Scholars know how to do:

If you don't find a counter, they have no equal.You are cowards and know little of this art. You are all words without any deeds. I challenge you to come at me one after another, if you dare, and even if there are a hundred of you, I will destroy all of you from this powerful guard.

Now come the players - the Master's replacement now wears a garter. The student makes a standard overhand strike, probably a flat snap, possibly a falling strike. The Master makes a broad full turn and brings the sword up using the momentum of the body to parry.

With a step, I have made a cover with my sword

And it has quickly entered into your chest.…I will advance my front foot a little off the line, and with my left foot I will step crosswise, and as I do so I will cross your swords, beating them aside and leaving you unprotected. I will then strike you without fail. And even if you throw your spear or sword at me, I will beat them all aside in the same manner I described above, stepping off the line as you will see me demonstrate in the plays that follow, and which you would do well to study. And even though I am only holding the sword in one hand, I can still perform all of my art, as you will see demonstrated in this book.

Thus, even though it looks like the Master's back is completely open, the line to attack down the middle is quickly and easily closed, and with very little deflection on the Master's part, the sword no longer has a target and is deflected slightly offline - and the Master is positioned to attack (remember - footwork sets up attacks!). This is a cover - the line is closed even when it looks like it's completely open.

So far what we have established is that period sources support a static shield defense - the large shield, above - an active shield defense - the buckler techniques of I.33 or Talhoffer - and both redirecting, or "shedding," parries and aggressive hard-block parries. I have elsewhere discussed, and hopefully the various images I have used from I.33, Yagyuu, and Fiore all show that period sources very strongly endorse mobility as a defense. Simply not being there is the easiest way not to be hit. Indeed, the signature technique of the Yagyuu school - their ability to fight an armed man while unarmed - is described by Yagyuu Munenori as consisting entirely of not being hit with your opponent's weapon, and everything else being situational (given that there are not one but two separate, very different, equally notable anecdotes about Munenori disarming his sparring partners, set fifty years apart, it is safe to say he knew what he was talking about on this one).

Now what about our best source from the SCA Period - which is to say, from 1968 to the present - Paul Porter, of the Bellatrix System? Porter is the only source I've ever found who discourages sword parries; he is emphatic that the best defense is to overwhelm your opponent's ability to attack in the first place, and the sword is better-served doing that. However, if you are defending yourself, he favors a technique called the punch-block, which I mentioned above in connection with I.33, and, as ever, denying the opponent the ability to hit you in the first place by controlling range and not being where they want you to be.

The punch-block, as described by Porter, possibly illustrated above, and drilled by me, consists of trying to reach out with the shield hand toward the opponent's sword hand. I try to point my index finger at my opponent's sword hand - the sword can change geometry, but the hand is on a pretty tight leash. This puts my shield boss into contact generally above their basket, or, if I am very lucky, the edge of my shield in the same position, from which I have a very small window in which I can maneuver their sword around - the German vor and nach in play; if I make the block, for that brief window I have the vor (the opponent's experience, incidentally, can make that window very brief, but not eliminate it entirely). This kind of block can be managed by a two-weapon fighter's offhand weapon, pushing the sword into a bind, but the vor window is even smaller there. A punch-block works best with a shield that recovers very quickly - my thirty-ish-inch round shield is near the upper limit of a center-grip that can accomplish it, though strapped shields can do it at virtually any size because the lever dynamics of the arm are different. Partly because of this, and partly because shields can obstruct your view as much as your opponent's, Porter recommends a strapped shield... you know what, I'm just going to show you, because there is nothing new under the sun.

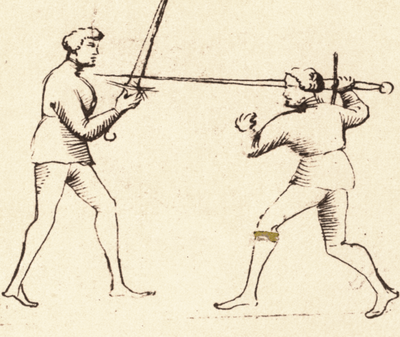

|

| Giacomo di Grassi looks confused. "I do WHAT with the sword?" |

Funny enough, di Grassi's text (modernized courtesy of Norman White) also reads like he endorses Paul Porter's Bellatrix stance:

Of the manner how to hold the round target

If a man would so bear the round Target, that it may cover the whole body, and yet nothing hinder him from seeing his enemy, which is a matter of great importance, it is requisite, that he bear it towards the enemy, not with the convex or outward part thereof, altogether equal, plain or even, neither to hold his arm so bowed, that in his elbow there be made (if not a sharp yet) at least a straight corner. For besides that (by so holding it) it wearies the arm: it likewise so hinders the sight, that if he would see his enemy from the breast downwards, of necessity he must abase his Target, or bear his head so peeping forwards, that it may be sooner hurt than the Target may come to ward it. And farther it so defends, that only so much of the body is warded, as the Target is big, or little more, because it cannot more then the half arm, from the elbow to the shoulder, which is very little, as every man knows or may perceive: So that the head shall be warded with great pain, and the thighs shall altogether remain discovered, in such sort, that to save the belly, he shall leave all the rest of the body in jeopardy. Therefore, if he would hold the said Target, that it may well defend all that part of the body, which is from the knee upwards, and that he may see his enemy, it is requisite that he bear his arm, if not right, yet at least bowed so little, that in the elbow there be framed so blunt an angle or corner, that his eyebeams passing near that part of the circumference of the Target, which is near his hand, may see his enemy from the head to the foot. And by holding the said convex part in this manner, it shall ward all the left side, and the circumference near the hand shall with the least motion defend the right side, the head and the thighs. And in this manner he shall keep his enemy in sight and defend all that part of the body, which is allotted unto the said Target. Therefore the said Target shall be born, the arm in a manner so straight towards the left side, that the eyesight may pass to behold the enemy without moving, for this only occasion, either the head, or the Target.

Short, less renaissance version - Hold your arm bent but mobile, hold it low enough that you can see over it without peeking, and hold the "bowl" of the shield out at an angle, not planed to the body. That is, in brief, Porter's shield stance. Porter would have a field day with di Grassi's sword, but that's a rapier, not an arming sword, so different strokes for different swords.

Every defense, then, is a mix of these three basic factors - armor (mostly for injury prevention), deflection, and mobility. After a while these start sounding like gaming terms, which shouldn't be that great a surprise given my background.

To summarize:

- Armor in the SCA does not prevent good blows. It prevents injuries.

- All defense in the SCA must be performed by the hands, body, and feet.

- The body and feet defend by moving out of the way. This requires an eye for the fight and a sense of timing. No one starts with these, they must be trained.

- The hands may either deflect with a shield, or by parrying with a sword.

- Shield protection varies by shield geometry - an entire separate discussion.

- Large shields offer more static protection but also a place for the enemy to hide.

- Large

shields tire the arm faster, all other things being equal, and require

more strength training (oh hi, Conditioning, did you think I'd forgotten

you?).

- Small shields offer less protection and require a more mobile, active deflection style.

- Parries, too, can be more or less static relative to the body - a cover - or dynamic - a block.

- Parries can be soft, mostly relying on redirection or "shedding," or hard.

- A hard block with a shield is generally called a punch block.

How do you train these? I recommend working at least a parry or block into every single partnered drill, deciding ahead of time which will be part of the drill, and then working through variations on them.

To drill "not being there," you can play tag in slow work - as you get used to not being where the sword is going, you speed it up, until someone decides it's too close to the real thing. This method, incidentally, has more modern endorsement as well - he wouldn't describe it thus, but it's what Dave Lowry describes in Autumn Lightning as the first lesson his sensei taught him after teaching him to pay attention to where the sword was. Considering what I said about the Yagyuu school's muto technique earlier, and that Lowry is a Yagyuu student, that shouldn't be terribly surprising.

Comments

Post a Comment