SCA Combat Curriculum Development - Structuring a Drill

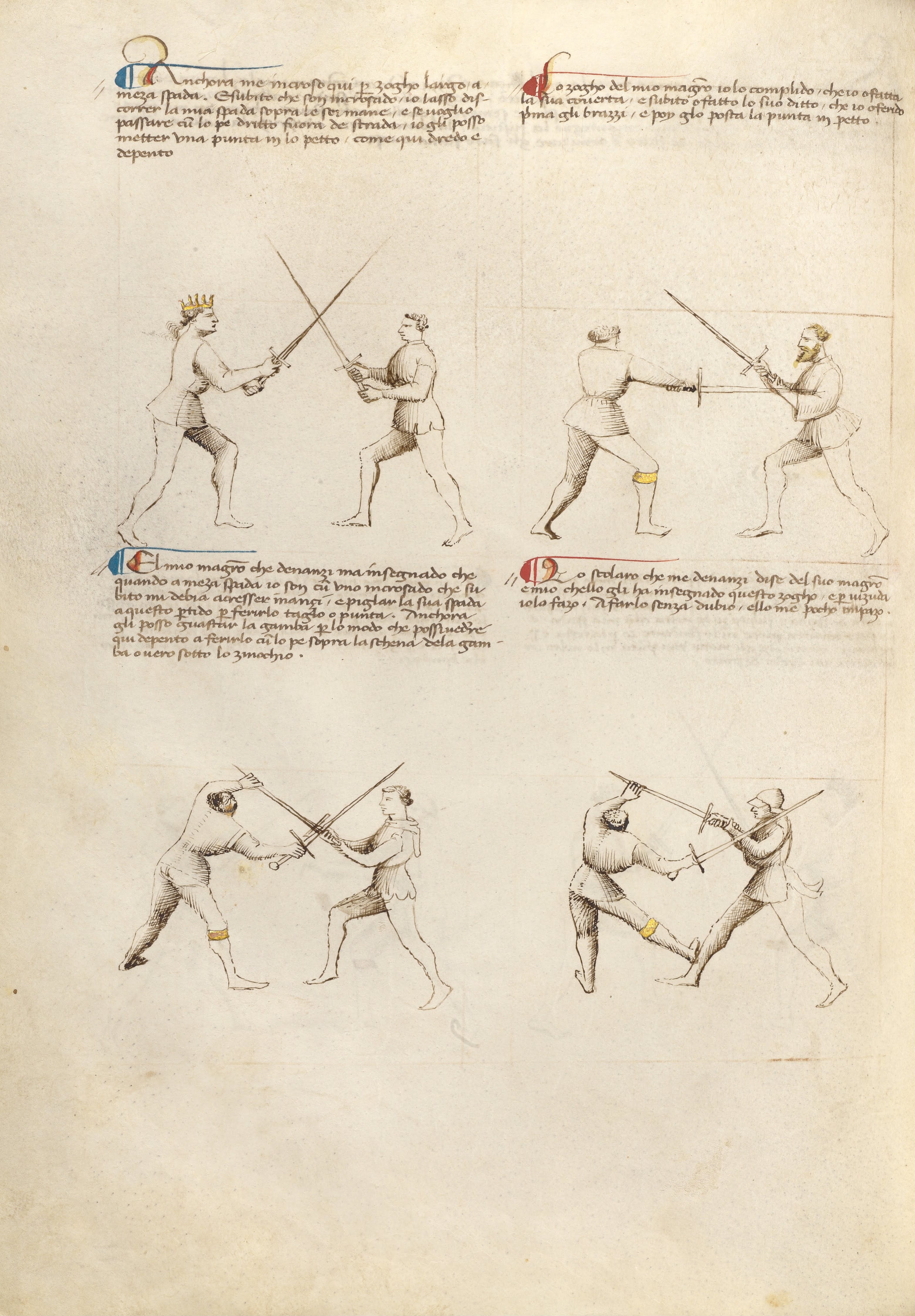

There are many ways to structure a drill. Guy Windsor's four-step approach - attack, defense, counter, counter-counter - has its roots in the layout of Fiore's Flower of Battle, where this was the basic structure of a page. Another approach is to separate the action into its individual beats, and use those as a counter; this is generally the easiest way to improvise a drill to teach an activity. I'm sure others will arise, but those are the two I've wound up using most frequently.

The first step in any training activity, though, is to define the objective. What are you trying to teach or learn with the drill, pell session, sparring, et cetera? Undirected practice is not practice, it's play. "Have fun" should always be one of the training objectives, but it is very often far down the list, given the amount of repetitive movement involved in drill work, pell work, et cetera. Instead, concrete examples - "today we are going to work on closure shots" - give training structure and clarity.

This is the point in a military exercise where I'd talk about Task, Conditions, and Standards. These three things are pretty standard to any learning method, but they're also jargon, so your own names can be substituted pretty much at will. These are just what I "grew up" with. The task is what the students are supposed to do - what you might otherwise call the lesson; the conditions are the starting assumptions of the lesson; the standards are what you might otherwise call the learning objectives. So let's assume for a moment that I'm discussing that closure shot above.

TASK: Cross into measure by an advance while throwing a closure shot with power.

CONDITIONS: Two students, each with shield (buckler acceptable) and sword, starting out of measure. Receiving student remains static throughout pass.

STANDARDS: Student is able to advance and throw closure shot safely at practice speed, without counters or reminders, at a static target with proper footwork and power three out of five times.

The way the Army would then deal with this would be to define the "school solution" to what a closure shot looks like, with diagrams and circles and arrows and (hopefully) a ton of pictures. Fortunately, Paul Porter already did most of the work on that for me, so I'll just refer you to the Bellatrix book for that. His format is pretty much what I'd expect from "FM 7-11: Sword Combat For The Individual." Note that no such book actually exists, FM 7-11 is, at the moment, not a real publication, so don't go looking for it (although its closest equivalent, Patton's 1914 saber manual, does contain useful information for drill structure and pell construction).

At this point, having established what you're trying to learn, you start breaking down the steps of how to learn it. For the above, there are several implied tasks: Can the student stand in stance? Can the student advance with clean footwork? Can the student throw a static shot? All of this assumes the answer to those questions is yes, but if these are not safe assumptions, then drills for those might be a better starting place.

Once the basic conditions for the drill to be appropriate to the student are met, you define what "right" looks like. Built into all of this, you should, as the designer, keep in the back of your mind which skills you're trying to build with this task. The closure shot drill, for instance, drills stance (maintain body posture), footwork (advance), attack (shot generation), and mental preparation (measure, combative attitude).

For this drill, those important instructional points might be - is the student advancing, rather than step-dragging or passing? Is the student maintaining good body position through the entire movement? Is the student using that advance to power the shot? Is the student finding the right measure? Is the shot selection reasonable and valid? Put together a list of questions, and then, on any given day, I would recommend having no more than three or four points to observe on any given drill. More than this, and the teacher will not track them all and the more points of correction you throw at them, the fewer the student will remember.

Now that you have your three or four points of emphasis, you think about what movements best emphasize that point - those are the areas that you want to exaggerate, if any, in your demonstration of the drill, because large, exaggerated movements are easier for students to pick up on, and it is easier to train a student to reduce a larger movement in a sequence, than to train a student to introduce a movement they just don't see you do in the first place when they learn the sequence. For instance, on the "throw closure shot" drill, it might be a good idea to throw at the very extreme of your range, to emphasize that closure range is longer than the student thinks, to stomp with the front foot as the sword connects, to emphasize that the sword and the foot are supposed to land together, or to assume much deeper knee-bend than you would assume in actual fighting, to emphasize that knees stay bent.

The above task - close into range while throwing a shot - is a single-beat activity, but I find it useful at this point, if possible, to separate the task into beats; in this case, beats are the separate, but linked, movements in a series. One of my basic principles is only do one thing at a time; just work at making the slices of time smaller. Windsor's four-count structure does this very well - it gives four beats, which can be called off one by one so the student knows which step is next in line. This allows the instructor, or training partner, to call off "one... two... three... four," then "one, two, three, four," then "one-two-three-four" until the exercise is moving fast enough that the caller is not required. An added benefit of this approach is that it teaches the mental skill of tempo (or, because I have a terrible sense of humor, "the rhythm of the fight" - oh yeah, it's the rhythm of the fight, listen to the rhythm of the fight...).

Now that the drill has structure, points of emphasis, and training objectives, you really should run through it with a sufficiently qualified partner before you try to teach it, preferably someone who thinks like you but isn't quite you, so they can tell you what, if anything, you're assuming that you shouldn't and whether the drill is teaching what you think it is. Run it from both sides - defender and attacker - so that you can see both sides of it. In this case, I recommend you run it as defender, so that you can see whether you can even observe your learning points, or whether you need to adjust how you observe them.

Once all the tinkering, testing, and adjustments have been made, the drill is ready to teach. As it is, you could stop there, but I recommend you don't. I recommend you think of variations on the drill, again ideally three or four of them so you don't overwhelm the student. On the closure-shot drill above, variations include "okay, can you hit me in the offside ribs?" or "okay, now can you do it on a moving target?" or "okay, I'm going to counter this time."

At this point, you're ready to run the drill live. We will discuss that, and feedback, next time.

Comments

Post a Comment