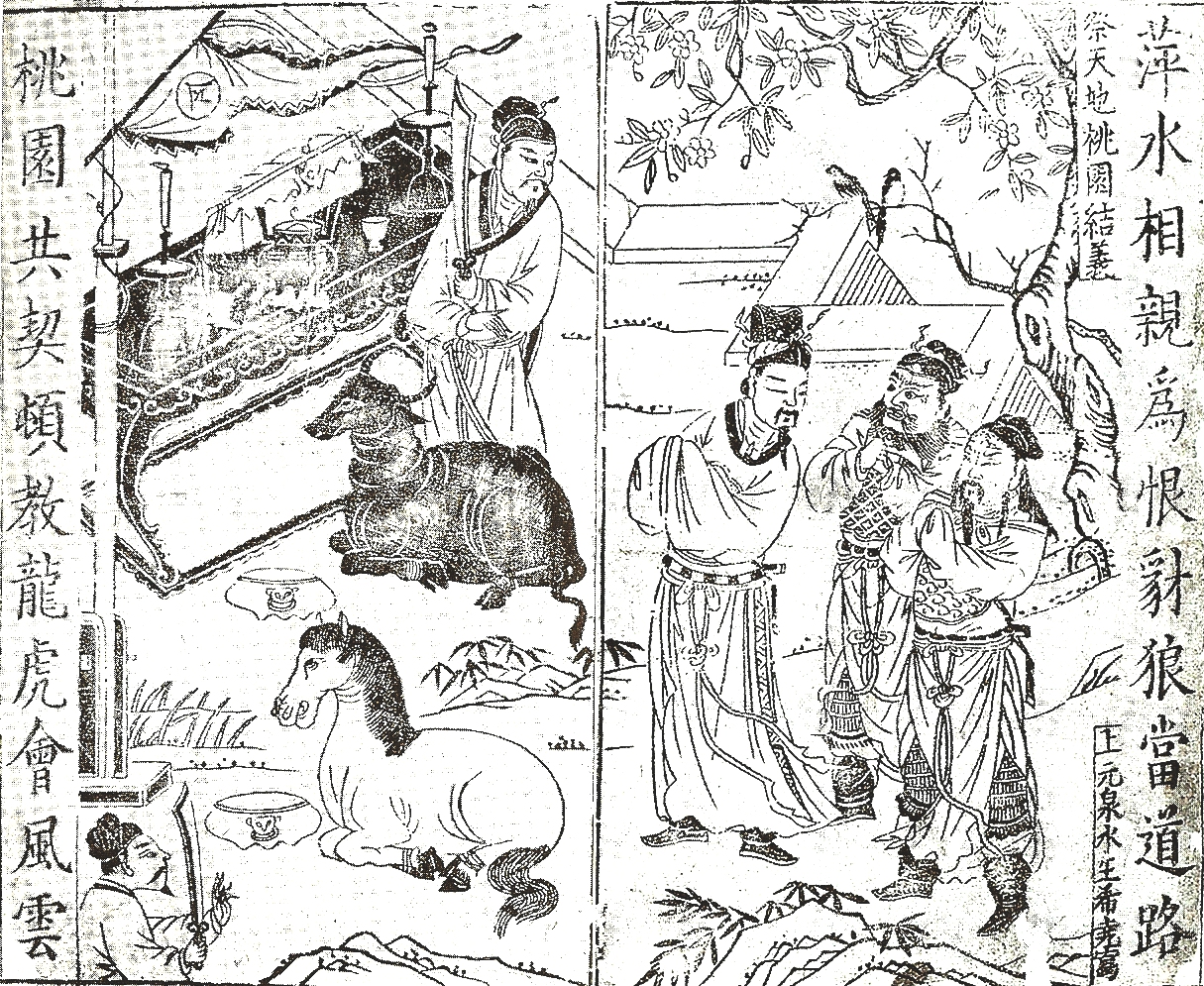

Profiles in Virtue - Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei - The Oath of the Peach Garden

|

| The gentleman on the left, observing the Oath, just wants to be done with the whole sworded affair. |

That event is the Peach Garden Oath, which brings together the hero and his two main supporters in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Before discussing the fictional version, one must separate the Romance from the very similarly titled Records of the Three Kingdoms. The Records was a respectable historical work, written very shortly after the reunification of the titular three kingdoms from primary documents, and was a scholarly work that included both moral lessons and strict recollection of facts. It can be thought of, broadly, as a parallel to Plutarch's Lives, since its structure is a series of biographies. It is also not fully available in English.

The Romance, on the other hand, is exactly what it sounds like - a novel, written by a playwright a thousand years after the fact. Taking the Romance as historically accurate is as viable as taking Richard III as an accurate rendition of the fall of the house of Lancaster. The majority of events in the Romance have a historical basis - the Peach Garden Oath, for instance, is not attested exactly, but its contents are plausible and its consequences are borne out by the Records - but that is somewhat like saying the Titanomachy must have a historical basis. It very well may, but it is very difficult to tell what that basis might be at this distance.

What the Romance does well is that it tells us what mattered to writers, and readers, of its time. Thus, the Peach Garden Oath is an important snapshot of what values mattered in China in the early 1300s. Just as William Marshal was a product of the period "when Christ and all His saints slept," and Richard III was a product of the Tudors, the Romance was composed in the early Ming Dynasty. The fall of the Yuan, and the rise of the Ming, was a period of violent upheaval, nationwide disruption, and local rule by warlords until a central government could impose its authority.

What mattered in this period? Historical evidence suggests legitimacy, stability, and continuity. The Hongwu Emperor made a deliberate call-back to pre-Yuan history, and despite being by some accounts a Buddhist monk prior to becoming a warlord, he emphasized Confucian themes - filial loyalty, correct relationships, and righteous behavior based on the examples of the past. This was a period where the imperial bureaucratic examinations reached their more or less final form, focused on study of classics and following a rigid essay form.

This informs the Peach Garden Oath. The Han Dynasty is in the throes of its final collapse after four hundred years. The Yellow Turban rebellion is in full swing, the imperial court is dominated by corrupt officials and eunuchs, and traditional values are everywhere neglected. Local warlords raise their own armies to attempt to establish local order and attempt to bring peace to the country. Three men enter a peach orchard with the intention of offering their own services to help with stabilizing China. One of these men is minor country gentry with an obscure pedigree, a cousin of the Han emperor, Liu Bei. One of them is a choleric giant with a massive beard, Guan Yu. The last, and youngest, is a wild and unpredictable drunkard, Zhang Fei. Together, they swear the following oath:

When saying the names Liu Bei,Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei, although the surnames are different, yet we have come together as brothers. From this day forward, we shall join forces for a common purpose: to save the troubled and to aid the endangered. We shall avenge the nation above, and pacify the citizenry below. We seek not to be born on the same day, in the same month and in the same year. We merely hope to die on the same day, in the same month and in the same year. May the Gods of Heaven and Earth attest to what is in our hearts. If we should ever do anything to betray our friendship, may heaven and the people of the earth both strike us dead.

The oath expresses what mattered at the time, both in the late Han and in the early Ming: establishing proper relations, bringing order and stability, and displaying mutual loyalty in the face of a confusing world. Nothing about this binds them to any particular warlord or even to the Emperor, though Liu Bei is expected, as a distant relative, to display at the very least filial loyalty to the extended clan. At this point, they have established that the three of them are a package deal. Worth noting, incidentally, is that the Hongwu Emperor, who established the Ming Dynasty, cast himself as country gentry with an obscure pedigree, interested in reestablishing the proper relations of the nation, ruler, and citizenry, prided himself on bringing stability to China, and viewed the court with deep suspicion.

From here, the three of them do indeed display the sort of mutual loyalty that the oath implies. They are not equals - Liu Bei's pedigree as an imperial relative, and being written as the Confucian beau ideal, means that he is the designated hero - but both Guan Yu and Zhang Fei speak bluntly to Liu Bei in the Romance, and even the historical records surrounding them indicate that they were so close that, especially in their early days, they shared a single bed in a single room as a matter of course. Both Guan Yu and Zhang Fei allow Liu Bei's hands to stay clean, most notably in the incident where Zhang Fei memorably beats a corrupt magistrate for trying to solicit a bribe from Liu Bei (the Records says Liu Bei did the beating, for comparison), or in the incident where Guan Yu tells Liu Bei point-blank he'd have been better-off assassinating Cao Cao on a hunt. They do not die on the same day - Guan Yu dies first, alternately receiving a standing death in battle, or being executed, depending on who tells the tale, then Zhang Fei is assassinated, then Liu Bei dies of disease and his son ruins the entire thing - but they die in the space of about three years, in a multi-generation story.

One of my purposes in writing this is highlighting values dissonance, between our values and their values for whatever "their" I am addressing, so I should spend a little bit of time on Liu Bei's son. Familial obligation was expected to trump most obligations, because whatever else Liu Bei was, he was definitely a Confucian. He was loyal to the emperor at least partly because they were related, in addition to the emperor bearing the Mandate of Heaven. However, a deliberate, chosen relationship, because it happened intentionally rather than by accident, trumped this obligation. Thus, when Liu Bei's family is captured, and Zhang Fei launches a daring counterattack to rescue them, it is somewhat shocking, especially to a modern audience, when Liu Bei throws his infant son to the ground angrily and reprimands Zhang Fei. His reasoning is the following, which became a proverb:

Brothers are like limbs, wives and children are like clothing. Torn clothing can be repaired; how can broken limbs be mended?

To a modern eye, dropping a baby on his head (thus, incidentally, dooming his dynasty - that's the son that ruins the entire thing) and reprimanding his follower for doing a thing to help him is pretty outrageous, but it makes sense in context. This is a period of civil war, and there are plenty of examples in the Romance of blood kin turning against each other; meanwhile, Zhang Fei and Guan Yu have, over and over again, proven that they take the Peach Garden Oath seriously. Men he could trust were indeed harder to replace than sons or wives. A loyalty that you chose trumps a loyalty that you were given.

This, I suspect, is a key component of this series of posts: Virtue is something that must be chosen, not something that just happens.

Comments

Post a Comment