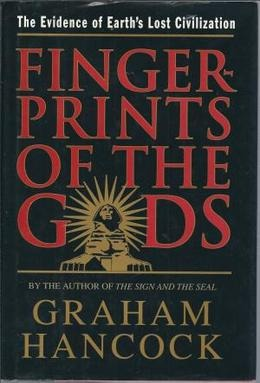

Book Review - "Fingerprints of the Gods," or Why I Hate Graham Hancock

Ideas are dangerous things.

In 1996, I was an extremely intelligent, but extremely inexperienced, teenager. The combinaton of intelligence and inexperience is important in this context, because it creates a target audience for a certain type of book, inviting the reader to believe they're part of some hidden knowledge. I read a lot of what I suppose could be called "conspiracy" books - Baigent, Lincoln, and Leigh's Holy Blood, Holy Grail, von Däniken, Sitchin, the whole nine yards. I've re-read many of them since, and found them almost universally full of steaming garbage. I've also watched them become increasingly mainstreamed - HBHG as Da Vinci Code. von Däniken and company explicitly in Ancient Aliens.

Then there is Graham Hancock.

A quick history - Hancock was a moderately successful journalist working in a variety of difficult, dangerous places on difficult, dangerous topics. He actually wrote a very good, and very successful, expose of the global aid industry in 1992 based on his experiences primarily in Africa. While working in eastern Africa during this period he became interested in the possibility that the Ark of the Covenant had been hidden in Lalibela, Ethiopia, and it was all downhill from there. From that point, his first "mystery" book, The Sign and the Seal, about the lost Ark, started him on a course of study that would lead him to claim a lost ancient super-civilization was responsible for seeding civilization worldwide. This has been the kernel of all of Hancock's subsequent work, and it was first explored in Fingerprints of the Gods,

There are, to say the least, problems with this idea.

I'm not going to go into Hancock's "white savior" issues or talk about how very few true pre-Conquest legends survive in Central America; on one hand, Hancock has walked the first back and I want to give him the benefit of the doubt, and on the other, the cleanest answer is we just don't know whether any given story involved bearded white men from beyond the sea before bearded white men showed up from beyond the sea. They might have, they might not, but it's just as impossible to ignore the invaders' impacts on native legend as it is to ignore the impact of the Norman Conquest on King Arthur.

Instead I am going to focus on the very specific problems of the Earth-crust displacement hypothesis of Charles Hapgood, which underpins the entire thing, because it is extremely easy to debunk the idea that Antarctica used to be tucked up in Africa's armpit. It's bad geology. Anyone who has ever moved a tent or other piece of textile across a piece of ground that they thought was free of snags can tell you why it's bad geology - even across an almost perfectly smooth piece of ground there will be small snags between the sliding sheet and the underlying surface. Those snags will produce behavior that's visible on the surface of the sheet. In the worst case, your tent tears. The underlying "hard science" of Hancock's thesis is that the Earth's crust shifted significantly approximately 14-12000 years before present, in a north-south motion with some rotation. If this were so, then we should see those snags, or evidence of major geologic events worldwide from about 14000 BP that could best be explained by a large crustal displacement - for instance, large rifts opened in the middle of the plates where snags happened. We don't see that.

There are other places where Hancock practices bad science, but the geology that underpins the entire thing is so egregiously bad that it's like building on a foundation of mayonnaise - the structure could be perfect, but it sinks instantly. A lot of the bad science is other people's that Hancock has bought into - Robert Schoch's geology of the Sphinx is, to say the least, controversial, and most of the sources that Hancock cites are "alternative," to put it politely. There's usually a single outlier data point that they latch on to, and then they build an entire hypothesis off of this point. If that data point is wrong, misinterpreted, or reinterpreted according to later information - well, Schwaller de Lubicz saw it in a dream in 1952, so everybody else must be wrong.

This brings us to the first of Hancock's truly cardinal scientific sins, cherry-picking. Evidence that doesn't conform to his hypothesis gets tossed aside, like the fact that we have ice cores from Antarctica that are generally agreed to be a few hundred thousand years old, so Antarctica has been at least partially ice-bound for that long, or the fact that Antarctica is home to living species with very significant evolutionary diversion, like the emperor penguin, that could not have happened in the last 12,000 years, or the fact that the Piri Reis map has its sources annotated on it.

There's a lot of evidentiary hand-waving in Fingerprints. One of the reasons that Schoch's geology of the Sphinx was discarded by mainstream Egyptology is because there was no supporting evidence of large-scale settlement at Giza during that time; in the thirty years since, there's been a lot of work to push back the frontier of prehistory on pre-dynastic Egypt and there still aren't any other data points saying that 12000 years ago, someone carved the Sphinx. That doesn't matter to Hancock, so it gets ignored; similarly, the fact that there are data points saying the Egyptians weren't "landlocked," like the elaborate depictions of boats and ships or the funerary barges of Khufu in the ship-tombs, or known trade with the Minoans, doesn't matter to Hancock; therefore they get ignored.

Now, all of that sounds like I'm going to say "don't read this book." I'm not. Hancock is well-read and well-traveled. He can be an engaging writer; if he had written a book themed, say, 101 Mysterious Places, and done a travelogue, he would've been in good shape, because he has an excellent ear for narrative details that ring true to the reader. Every account I've seen so far, from things like the production of his Netflix show Ancient Apocalypse, says that in conversation, he is perceptive and intelligent, and asks smart questions. The idea of a purely human prehistoric super-civilization certainly sounds more plausible than claiming everything was aliens, and Hancock assembles a Potemkin village of facts, and as long as you only ride down the main street, everything looks good. Where Hancock falls apart is that he doesn't leave main street of his Potemkin village, he doesn't explore the underlying science or really probe the implications of his ideas.

This is different from, say, Erich von Däniken. He's an obvious con artist (as in, convicted in Swiss court of embezzlement and fraud); like the best con artists, when he is saying things, he believes in it and facts be damned, and because he only needs to believe what he's saying at this very moment, it doesn't matter if it contradicts something else he's said, because he's moved between cons. He's a used car salesman, it just so happens that his used cars are UFOs in the deep past. Hancock has a bad idea and sells it convincingly because he's assembled what is to him a coherent, cohesive structure to support it, and he is eloquent and articulate enough to make it look convincing. Unfortunately, even when presented with strong counter-arguments, he's proven to be less interested in adapting to facts, than adapting facts to his narrative, and enough people find his narrative persuasive that it weakens the credibility of the underlying facts. That, not a lack of ability, is why I hate Graham Hancock.

Comments

Post a Comment